Essentially, experimental archaeology means trying to replicate the ancient method by taking the clues we have and trying out various scenarios in the present. In the process, you hope to learn more about just how the ancient beverage was made.

Essentially, experimental archaeology means trying to replicate the ancient method by taking the clues we have and trying out various scenarios in the present. In the process, you hope to learn more about just how the ancient beverage was made.

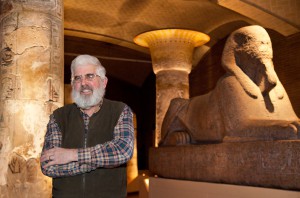

For example, Midas Touch came about when I decided to have a competition among microbrewers who were attending a “Roasting and Toasting” dinner in honor of beer authority Michael Jackson (not the entertainer, but the beer and scotch maven, now sadly no longer with us) in March of 2000 at the Penn Museum.

I simply got up at the dinner, and announced to the assembled crowd that we had come up with a very intriguing beverage that we needed some enterprising brewers to try to reverse-engineer and see if it was even possible to make something drinkable from such a weird concoction of ingredients. Soon, experimental brews started arriving on my doorstep for me to taste–not a bad job, if you can get it, but not all the entries were that tasty. Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head Brewery ultimately triumphed.

Sam Calagione, along with Mike Gerhart and Bryan Selders, with experimental prowess the equal of any Neoltihic beverage-maker, brought Chateau Jiahu back from the dead.

Watch the video “Burton Baton and the Legend of the Ancient Ale” that garnered first prize at the Off-Centered Film Fest in Austin, TX:

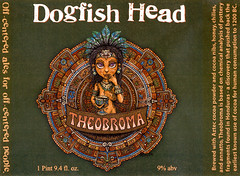

| Theobroma This beer is based on chemical analysis of pottery fragments found in Honduras which revealed the earliest known alcoholic chocolate drink used by early civilizations to toast special occasions. The discovery of this beverage pushed back the earliest use of cocoa for human consumption more than 500 years to 1200 BC. As per the analysis, Dogfish Head’s Theobroma (translated into ‘food of the gods’) is brewed with Aztec cocoa powder and cocoa nibs (from our friends at Askinosie Chocolate), honey, chilies, and annatto (fragrant tree seeds). It’s light in color – not what you expect with your typical chocolate beer. Not that you’d be surpised that we’d do something unexpected with this beer! Read more |

|

| Chateau Jiahu Let’s travel back in time again (Midas Touch was our first foray and Theobroma our most recent), this time 9000 years! Preserved pottery jars found in the Neolithic villiage of Jiahu, in Henan province, Northern China, has revealed that a mixed fermented beverage of rice, honey and fruit was being produced that long ago – right around the same time that barley beer and grape wine were beinginning tobe made in the Middle East! Read more |

|

| Midas Touch All of the ideas about what our ancient ancestors were drinking–whether a wine, beer, or mead–come together in our research on the so-called King Midas funerary feast, because surprisingly all three were mixed together in the drink. Read more |

|

| Chicha Throughout the last 15 years we have brewed over 200 different off-centered ales here at Dogfish Head. A number of our beers have been based on archeological evidence or researching ancient brewing traditions. We have now made what we believe is one our most exotic and unique beer yet. Chicha is the quintessential native corn beer throughout Central and South American. Indigenous versions with local variations exist in Chile, Bolivia, Colombia and many other countries. Read more |

Midas Touch

All of the ideas about what our ancient ancestors were drinking–whether a wine, beer, or mead–come together in our research on the so-called King Midas funerary feast, because surprisingly all three were mixed together in the drink. The gala re-creation of the feast in 2000 was at the Penn Museum. A spicy, barbecued lamb and lentil stew, according to our chemical findings, was the entree, and it was washed down with a delicious, saffron-accented rendition of the Phrygian grog or “King Midas Golden Elixir” by Dogfish Head Craft Brewery. Dogfish is the fastest growing microbrewery in the country, and “Midas Touch” has become its most awarded beverage (3 golds and 5 silvers in major tasting competitions, with a few bronzes tossed in for good measure). The extreme beverage took another silver in the Specialty Honey Beer category at the 2013 Great American Beer Festival in Colorado.

It all started with a tomb, the Midas Tumulus, in central Turkey at the ancient site of Gordion, which was excavated by this Penn Museum in 1957, over 50 years ago. The actual tomb, a hermetically sealed log chamber, was buried deep down in the center of this tumulus or mound, which was artificially constructed of an enormous accumulation of soil and stones to a height of some 150′. It’s the most prominent feature at the site. There was indeed a real King Midas, who ruled the kingdom of Phrygia, and either him or his father, Gordius, was buried around 740-700 B.C. in this tomb. There’s still some uncertainty, since there’s no sign announcing “Here Lies Midas or Gordius!”

When the Penn Museum excavators cut through the wall, they were brought face-to-face with an amazing sight, like Howard Carter’s first glimpse into Tutankamun’s tomb. The excavators first saw the body of a 60-65-year-old male, who had died normally. He lay on a thick pile of blue and purple-dyed textiles, the colors of royalty in the ancient Near East. In the background, you will see what really got us excited: the largest Iron Age drinking-set ever found–some 157 bronze vessels, including large vats, jugs, and drinking-bowls, that were used in the final farewell dinner outside the tomb.

Like an Irish wake, the king’s popularity and successful reign were celebrated by feasting and drinking. The body was then lowered into the tomb, along with the remains of the food and drink, to sustain him for eternity or at least the last 2700 years.

None of the 160 drinking vessels, however, was of gold. Where then was the gold if this was the burial of Midas with the legendary golden touch? In fact, the bronze vessels, which included spectacular lion-headed and ram-headed buckets for serving the beverage, gleamed just like the precious metal, once the bronze corrosion was removed. So, a wandering Greek traveler might have caught a glimpse of this when he or she concocted the legend.

The real gold, as far as I was concerned, was what these vessels contained. And many of them still contained the remains of an ancient beverage, as seen in this close-up photograph of the residue, which was intensely yellow, just like gold. It was the easiest excavation I was ever on. Elizabeth Simpson, who has studied the marvelous wooden furniture in the tomb, asked me whether I’d be doing the analysis. I just had to walk up two flights of stairs, and there were the residues in their original paper bags from when they were collected in 1957 and sent back to the museum. We could get going with our analysis right away.

What then did these vessels contain? Chemical analyses of the residues–teasing out the ancient molecules–provided the answer. I won’t go into all the details of our analyses, in the interests of the chemically-challenged (please refer to the attached pdf’s). Briefly, by using a whole array of microchemical techniques, including infrared spectrometry, gas and liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, we were able to identify the fingerprint or marker compounds for specific natural products.

These included tartaric acid, the finger-print compound for grapes in the Middle East, which because of yeast on the skins of some grapes will naturally ferment to wine, especially in a warm climate. The marker compounds of beeswax told us that one of the constituents was high-sugar honey, since beeswax is well-preserved and almost impossible to completely filter out during processing; honey also contains yeast that will cause it to ferment to mead. Finally, calcium oxalate or beerstone pointed to the presence of barley beer. In short, our chemical investigation of the intense yellowish residues inside the vessels showed that the beverage was a highly unusual mixture of grape wine, barley beer and honey mead.

You may cringe at the thought of mixing together wine, beer and mead, as I did originally. I was really taken aback. That’s when I got the idea to do some experimental archaeology. In essence, this means trying to replicate the ancient method by taking the clues we have and trying out various scenarios in the present. In the process, you hope to learn more about just how the ancient beverage was made. To speed things up, I also decided to have a competition among microbrewers who were attending a “Roasting and Toasting” dinner in honor of beer authority Michael Jackson (not the entertainer, but the beer and scotch maven, now sadly no longer with us) in March of 2000 at the Penn Museum.

I simply got up at the dinner, and announced to the assembled crowd that we had come up with a very intriguing beverage that we needed some enterprising brewers to try to reverse-engineer and see if it was even possible to make something drinkable from such a weird concoction of ingredients. Soon, experimental brews started arriving on my doorstep for me to taste–not a bad job, if you can get it, but not all the entries were that tasty.

Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head Brewery ultimately triumphed. He also came up with an innovative label of our re-created beverage, showing the Midas golden thumb print.

Just one footnote: the bittering agent used in Midas Touch was not hops (which was only introduced in to Europe around 700 A.D.), but the most expensive spice in the world, saffron. Turkey was renowned for this spice in antiquity, and although we’ve never proven it, the intense yellowish color of the ancient residues may be due to saffron.

Chateau Jiahu

An extreme beverage like Midas Touch, once lost and now rediscovered, made me wonder: just how early were humans making and drinking fermented beverages and why have humans had a seemingly millennia-long love affair with alcoholic beverages around the world?

If you think about it and even if you don’t have any firm chemical evidence, you might surmise that members of our species, even 100,000 years ago, were probably already making beers, wines and extreme beverages from wild fruits, honey, chewed grains and roots, and all manner of herbs and spices culled from their environments. After all, our ancestors had much the same sensory organs and brains as we do, and they would have known what they liked.

We are narrowing in on the prospect of discovering fermented beverages from the Palaeolithic period, and one recent discovery illustrates how you should never give up hope and that research very often has big surprises in store. You might think, as I did too, that the grape wines of Hajji Firuz, the Caucasus, and eastern Anatolia would prove to be the earliest alcoholic beverages in the world, coming from the so-called “Cradle of Civilization” in the Near East as they do. But then I was invited to go to China on the other side of Asia, and came back with samples that proved to be even earlier–from around 7000 BC (that’s 9000 years ago). There, at the Neolithic site of Jiahu in the Yellow River valley, the people were making, enjoying, and using what is so far the earliest chemically attested fermented beverage in the world in their burial and religious ceremonies. Like Midas Touch, it was another take on an extreme fermented beverage, and it illustrates once again the hold that alcoholic beverages have on the human race.

Most importantly, China began making pottery earlier than in the Near East (as early as 13,000 BC versus 6000 BC), and this was crucial to our discovery. Pottery is virtually indestructible, and liquids are absorbed into the pores of the pottery. As a result, ancient organics are preserved for 1000’s of years until we come along to extract and analyze them.

The pottery that we analyzed from Jiahu were jars with high necks, flaring rims and handles, which were ideally shaped to hold and serve liquids. Again, we used a whole battery of chemical tests to ferret out the original beverage (see pdf).

You could call this extreme beverage a “Neolithic grog.” It was comprised of honey mead and a combined “beer” or “wine” made from rice, grapes, and hawthorn fruit. Rice is a grain, like wheat and barley, so by that definition it makes a beer (of about 4-5% alcohol), but when it’s fermented to 9-10% and has pronounced aromatic qualities, then it’s more like a wine. Maybe, the best modern comparison is with an aged Belgian ale or a barley wine. Although some ingredients have been interchanged, it’s also not all that different from Midas Touch in combining a wine, beer and mead, even if Jiahu precedes Midas by some 6000 years.

One topic ripe for discussion is how did it happen that China now has the earliest chemically attested instance of grape being used in a fermented beverage? Of course, the use of grape this early–likely a wild Chinese species such as Vitis amurensis with up to 20% simple sugar by weight–came as a great surprise. As far as we know–but continued exploration may change the picture–none of some 40 grape species found in China, the highest concentration in the world, were ever domesticated. Yet, this is the earliest evidence of the use of grape in any fermented beverage. And high-sugar fruit, with yeast on its skins, is crucial in making the argument that the liquid in the vessels wasn’t just some kind of weird concoction but actually was fermented to alcohol by the yeast.

We don’t know at this point whether hawthorn fruit or grape alone or in combination were used. After we announced that these were the most likely fruits based on our chemical results, a study of the botanical materials at the site–a discipline that has recently begun to be practiced in China–seeds of just those two fruits and no others were found. Although not helping us to decide whether either or both were used for the beverage, this provided excellent corroboration for our findings.

We could debate whether the rice in the Jiahu beverage was wild or domesticated, and whether its starch was broken down by chewing or malting. Chewing or salivating a grain, stalk or tuber to break down its starches into sugar appears to the be earliest method that humans employed for preparing their beers around the world. An enzyme–ptyalin–in human saliva acts to cleave the larger molecules into simple sugars. In modern Japan and Taiwan, communities of women still gather around a common vessel, and chew and ferment rice wine for marriage celebrations. Corn beer or chicha in the Americas is still made this way.

However the rice was broken down and fermented, it still leaves lots of debris that floats to the surface, and the best way around that is to use a drinking-tube or straw, the time honored method to drink beer in ancient Mesopotamia and here rice wine in a traditional village of south China.–what you might call extreme beverage-drinking.

Jiahu wasn’t just your run-of the-mill early Neolithic site. It has yielded the earliest playable musical instruments in the world, three dozen of them made exclusively from one wing bone of the red-crowned crane. The flautist for Beijing’s Central Orchestra of Chinese Music has shown that the flutes will play the traditional Chinese pentatonic scale and its music. The flutes might well have played a role, along with the fermented beverage, in ceremonies to the ancestors, just like music and rice and millet wine were closely associated with ancestor worship at the fabulous Shang Dynasty capital cities, such as Anyang, from about 1600 to 1050 BC, and up to present.

Our re-created Neolithic beverage, which is called Chateau Jiahu, is of course named after the site in China where the pottery was excavated that led to our analysis and reconstructing the ancient recipe. And at the recent 2009 Great American Beer Festival, it garnered a gold medal in a blind tasting competition, which was followed up with a silver in 2011. This is very appropriate as the earliest alcoholic beverage in the world. Sam and I went together onto the podium to receive the medal, and it’s now set up as a small shrine in my laboratory.

Its label, inspired by a dream Sam had, clearly pushes the envelope visually, as does the extreme beverage inside the bottle. The seemingly enigmatic tattoo that graces the lower back of our celebrant on the bottle is actually the Chinese sign for “wine” and other alcoholic beverages. It shows a jar with three drops of liquid falling from its lip. The sign dates back to the Shang Dynasty and has been in continuous use ever since.

Fresh whole hawthorn fruit, muscat grapes (since we have not yet been able to obtain wild grapes from China), orange blossom honey, and gelatinized rice malt with their hulls were brewed together and fermented with an American ale yeast. You’ll be glad to know that the rice was not saccharified by chewing–Sam said he was ready to do that if that was what they did in antiquity. But they could also have malted the rice, so we went with that. The beverage has a marked sweet-and-sour profile, which goes extremely well with Asian cuisine.

Theobroma

Our ancestors might well have brought traditions of how to make a fermented beverage with them to the New World, but they were also faced with harnessing the resources of a host of new plants– maize or corn, cacti of all kinds, manioc or cassava and squash, and much, much more. My laboratory’s most recent finding of some of the earliest chocolate or cacao is an excellent example of how a new alcoholic beverage was discovered and put to use (see pdf).

The famous Swedish botanist, Linnaeus, is the one who gave the tree and its fruit it wondrous name Theobroma cacao in Latin, Theobroma meaning “food of the gods.” When the fruit has a warty skin, this marks it as belonging to the very delicious and aromatic criollo variety from Mesoamerica. Juicy pulp surrounding 30 to 40 almond-shaped seeds or “beans” fills each pod. It is this sweet pulp, with as much as 15% sugar, that we think first attracted our ancestors to the plant and eventually led to its domestication. Fermentation of ripe fruit occurs naturally, and produces a 5 to 7% alcoholic beverage. In fact, this is the way that the beans are freed from the pod in modern chocolate production. The Spanish chroniclers observed that native peoples along the Pacific coast of Guatemala delighted in a mildly alcoholic beverage, which they made by piling cacao fruit into their dugout canoes and letting it ferment there.

We, and by we I’m also including fellow-scientist Jeff Hurst at Hershey Chocolate, analyzed pottery sherds belonging to long-necked jars. Such vessels from Honduras are among some of the earliest pottery yet found anywhere in Mesoamerica, dating back to around 1400 B.C. They preceded the first urban communities of the Olmecs, centered on the Gulf Coast of what are now Mexico’s Veracruz and Tabasco provinces.

Vessels of the long-necked jar type from Puerto Escondido tested positive for theobromine, which is the fingerprint compound for cacao since the compound only occurs in chocolate fruit and beans in Mesoamerica. The style of the vessel was another give-away or advertisement of its contents–it had the shape and characteristic ridges and indentations of the cacao fruit. What we propose, based on the chemical and archaeological evidence, is that the jar was once filled with a fermented chocolate beverage made from ripe chocolate fruit.

In later Mesoamerica, the Mayans and then the Aztecs increasingly turned to the beans, rather than the fruit, to make their cacao beverage. They also mixed in lots of additives–honey, chilis of all kinds, variously scented flowers, and achiote or annatto (Bixa orellana) which colors the beverage an intense red in keeping with its association with human sacrifice. If a victim atop one of the pyramids faltered, he was given a gourd of chocolate, mixed with blood which had been caked on the obsidian blades of earlier sacrifices.

This later drink was often frothed to give a high head of foam, which can be seen on Mayan frescoes. The idea was apparently to inhale the foam at the same time that one drank the liquid directly from the mouth of the vessel.

When we analyzed the Puerto Escondido jars and bowls, we made a special attempt to identify any of the later additives. None were present, providing a stronger case that the earliest beverage, made only from the fruit, paved the way for the foamy Mayan-Aztec drink made from the beans.

Like grape wine, rice wine, and barley beer in the Old World, chocolate “wine” went on to become the prerogative of royalty and the elite generally, and a focus of religion in the New World. Cacao beans also served as money for the Aztecs, and King Montezuma had a veritable Fort Knox in his storerooms at Tenochtitlan–nearly a billion beans, according to one Spanish informant.

Many of the most stunning pottery vessels from Mesoamerica were made to hold the beverage, like the beautifully decorated and unique jar from a tomb (Rio Azul) in Guatemala, dated to around 500 A.D. It actually has a swivelling, lock-on lid, to protect and selectively dole out its precious liquid. Jeff Hurst confirmed that the liquid was a chocolate beverage. The Mayan hieroglyph for ka-ka-w (“cacao”) was written on the vessel; it shows the head of a fish and a fin, both pronounced ka–hence, ka-ka-w.

If a fermented chocolate beverage was good enough for Montezuma to drink in the 16th c.–he reputedly was served 50 great jars of it at a banquet with 300 dishes–and long before that at Puerto Escondido, then why not try and re-create a modern version of the ancient beverage? Just like we had done before, we enlisted the aid of Dogfish Head Brewery.

Since it proved impossible to transport the fresh fruit without spoilage from Honduras, we did the next best thing. We were able to obtain chocolate nibs and powder from the premier area of Aztec chocolate production, Soconusco, the first such dark chocolate to be imported into the States in centuries (Askinosie Chocolate in Missouri). As you drink this luscious beverage–almost like a fine Scotch or Port–you will pick up the aroma of the cacao and hints of the ancho chili in the aftertaste. Any bitterness of the chocolate is offset by the honey and corn. Achiote colors it red. It was fermented with an American ale yeast.

Of course, we named the chocolate beverage Theobroma, since it is truly an elixir of the gods–as suggested by the image on its label of ab Aztec maiden set among the gods of the four quarters of the universe.

Chicha

The transformation of corn (maize) into beer or chicha was a monumental achievement of the early Americans, comparable to the conversion of cacao fruit and beans into a beverage. Like cacao, Chicha, too, was to become an elite beverage that powered its own “Neolithic Revolution.” Wherever it went, from Central to South America, it became imbued with social, economic, and supernatural significance. The earliest pottery from South America, dating back to ca. 5000 B.P., was likely intended for chichas, primarily made from corn but also manioc, wild fruits, cacti, potatoes, ad infin.

Chicha’s importance in the social and religious world of Archaic America can best be appreciated by focusing on the drink’s central role in the much later Inca empire of Peru.

Corn (Zea mays) was a sacred crop for the Incas and their predecessors. Chicha, in particular, was considered very high status. In late prehistory, huge local and state farms, the majority on steep, terraced hill slopes and irrigated plains of the deserts and valleys, were dedicated to the production of corn. This work was largely powered by chicha, viz., the local populaces carried out the work in exchange for chicha and other benefits from the their rulers. Chicha was consumed in great quantities during and after the work, making for a festive mood of singing, dancing, and joking.

Chicha was offered to gods and ancestors, much like other fermented beverages around the world were. For example, at the Incan capital of Cuzco, the king poured chicha into a gold bowl at the navel of the universe, an ornamental stone dais with throne and pillar, in the central plaza. The chicha cascaded down this “gullet of the Sun God” to the Temple of Sun, as awestruck spectators watched the high god quaff the precious brew. At most festivals, ordinary people participated in days of prodigious drinking after the main feast, as the Spanish looked on aghast at the drunkenness.

Human sacrifices first had to be rubbed in the dregs of chicha, and then tube-fed with more chicha for days while lying buried alive in tombs. Special sacred places, scattered throughout the empire, and mummies of previous kings and ancestors were ritually bathed in maize flour and presented with chicha offerings, to the accompaniment of dancing and panpipe music. Even today, people Peruvians sprinkle some chicha to “mother earth” from the communal cup when they sit down together to drink; the cup then proceeds in the order of each drinker’s social status, as an unending succession of toasts are offered.

Our latest endeavor with Dogfish Head was to make a truly American corn beer or chicha by chewing the native Peruvian red corn, spitting it out, and fermenting. Pepper berries and strawberries piquant and aromatic touches, and made for a delicious beverage which was a hit at the 2009 Great American Beer Festival and other events.