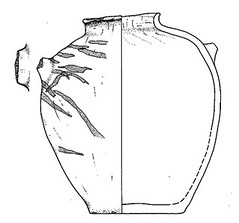

- Lidded you jar from the Changzikou Tomb in Luyi county, Henan province, dated ca. 1250–1000 B.C.–here opened. (Photograph courtesy of Z. Zhang and Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology of Henan Province).

Wines Fit for Kings and the Afterlife

My laboratory, in collaboration with colleagues at Penn’s Abramson and Medical Centers, is now testing compounds in ancient fermented beverages for their anti-cancer and other medicinal properties in a new project called “Archaeological Oncology: Digging for Drug Discovery.” Our ancient ancestors had a huge incentive in trying to find any cure they could to cure mysterious diseases and extend their life spans beyond the usual 20-30 years. Over millennia, they might well have hit upon solutions, even if they couldn’t explain it scientifically. Superstition also crept in, but in certain periods, like the Neolithic, humans were remarkably innovative in domesticating and probably discovering medicinal plants. They were lost to future generations when the cultures collapsed and disappeared, but can now be rediscovered using Biomolecular Archaeology.

Prehistoric Egypt illustrates the phenomenon, which likely extends far back in the past, to the beginnings of our species. During Dynasty 0, around 3150 B.C., one of the first kings of Egypt, Scorpion I, was buried in a magnificent “funerary house” in the desert at Abydos on the middle Nile River.

The German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo excavated Scorpion’s tomb in all its splendor, with ivory scepter and supplies of food and drink to carry with him into the afterlife. What was most astounding was that 700 jars containing some 4500 liters of resinated wine, according to our chemical analyses, were deposited in these three rooms, which was then covered over by a roof and mound of earth.

The jars were filled with sand when they were found. Once the sand was poured out from each jar, rings of a yellowish crusty residue were revealed on the interiors of the jars. The rings or tide-lines were slanted off from the horizontal, and are best explained as the remains of a liquid that had gradually evaporated, with materials on the surface of the liquid agglomerating to form the rings. Some of the jars also contained something highly unusual that had never been seen before: figs had been sliced up and perforated to run a string through them so that they could be suspended from the mouth of the vessels into the liquid. The preservation of figs, more than 5000 years old, is quite amazing. It is not attested for any other ancient wine, although it might well have served as a sweetening or fermenting agent or special flavoring; by cutting up and stringing out the fig segments, more of the wine would come in contact the fruit.

Where had such a large quantity of for Scorpion I’s trip through eternity, come from? The extremely dry terrain of Abydos was an unlikely place to have transplanted the domesticated grapevine and produced wine. Moreover, the Eurasian grapevine never grew in Egypt until it was transplanted there and the basis of royal wine industry around 3000 B.C.

Our analyses by neutron activation analysis of the pottery comprising the jars themselves provided the answer. The tests showed that they were made from clays local to the Jordan Valley and the southern hill country to its west and Transjordan to the east. Assuming that the jars were made in the same places that the wine was produced, it is now clear that the wine deposited in the tomb of Scorpion at Abydos was transported some 500 to 700 miles, overland by donkey caravans, including the Sinai stretch (the so-called “Ways of Horus”) of ten days, and then probably by boat up the Nile. This scenario makes good sense, since we know that the Levantine winemaking industry had already been in existence for a thousand years.

What appears to be happening in the earliest stages of Egyptian history is that the rulers and upper classes began to import wine as a costly, prestige item, not unlike what goes on today when we serve that special bottle to friends–whether a Pétrus, a lush Priorat or Rioja wine, or Egyptian “Cleopatra,” still made in the Nile Delta. Even though it must have been like importing liquid gold, the Egyptian rulers at first had no choice but to procure the beverage from the nearby Levant with its well-established winemaking industry. The main impetus for this development was what can be called “elite emulation.” Wine and special wine-drinking vessels were given as gifts to kings and the upper class. The Pharoahs knew that rulers elsewhere in the Near East celebrated their victories with special wine-drinking ceremonies, offered wine to the gods as an evocative symbol of blood in their role as high priest, and stocked their tombs with the elixir. In imitation of this conspicuous consumption, one king after another adopted the wine culture.

Once the beverage had established an economic foothold, usually being incorporated into religious ritual and social custom as well, the next logical step was to transplant the grapevine itself, and begin producing wine locally to assure a more steady supply, at a lower cost and tailored to local tastes. The Nile Delta with its extensive tracts of irrigated land, sunny days and short rainy season was ideal, and became the focus of the royal wine industry in the first two dynasties.

Besides being resinated wine with terebinth tree resin to which fresh fruit (grapes and figs) had been added, the Scorpion wine had also been laced with a variety of herbs–mint, coriander and sage–according to our re-analysis of the jar residues, using state-of-the-art techniques in collaboration with the U.S. Government Tax and Trade Commission Laboratory (Beltsville, MD).

We have also demonstrated that the liquid in the jars had indeed been fermented, according DNA analysis in collaboration with the University of Florence. The residues revealed fragments of wine yeast DNA, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the earliest ever recovered and the likely precursor of the bread and beer yeasts.

Egypt has one of the most ancient and detailed materia medica in the world, based on archaeobotanical findings and literary traditions. Papyri, dating back to the mid-12th Dynasty, ca. 1850 B.C., show that “medicinal wines” were very important to the Egyptian “physician” (swnw, the hieroglyphic word, is attested as early as Dynasty 3, ca. 2650 B.C.).

More than a thousand prescriptions are recorded in the ancient Egyptian medical papyri. Most numerous are those that list alcoholic beverages–wine and beer–as dispensing agents, and in which tree resins (terebinth, pine, frankincense, myrrh, fir, etc.) and numerous herbs (bryony, coriander, cumin, mandrake, dill, aloe, wormwood, etc.) are added ingredients. The plants and their exudates were macerated, mixed together, and steeped in these beverages; they were administered for specific ailments. Traditional Egyptian medicine today still uses many of the same formulations. Based on the continuity of Egyptian medicine over thousands of years, it is reasonable to project it further back into the past, to account for the biomolecular and archaeobotanical evidence from the Scorpion I wine jars.

Our earliest evidence of an alcoholic beverage from anywhere in the world, which might have been used medicinally, is from the Neolithic site of Jiahu in the Yellow River Valley of China, dating back to ca. 7000 B.C. Biomolecular archaeological analyses of pottery jars which contained the beverage showed that the ancient beverage had been formulated from rice, honey, a Chinese grape species, and hawthorn tree fruit. This finding is obviously of great interest for the history of Chinese medicine, which was already being written down in the earliest texts–the oracle bone inscriptions of the late Shang Dynasty (ca. 1200-1046 B.C.)–and then continued to develop over the next three millennia to become TCM. In recent decades, the latter has been put on a much more solid scientific basis. Since we have not yet analyzed the extracted residues from the Jiahu jars by the same techniques used recently for the Scorpion wine, it is not known whether any herbs or spices, which might have anticancer or other medicinal properties, were added to the ancient mixed beverage. Other than several well-known and studied anti-oxidant compounds from grape (e.g., resveratrol) and hawthorn fruit, our survey of the literature did not reveal any additional active anticancer compounds to be screened.

By Shang Dynasty times, however, herbs were clearly part of an already highly specialized medicinal wine “industry.” One wine (chang) was specifically denoted as herbal wine in the oracle bone inscriptions. Officials in the Shang palace administration were charged with making the beverages, which the king inspected. Our Thermal Desorption GC-MS analysis of liquid, amazingly still contained inside a lidded bronze jar (Fig. 2) from the Changzikou Tomb in Henan Province (ca. 1050 B.C., contemporaneous with the oracle bone inscriptions), illustrates what information can be gleaned via biomolecular archaeology. The tight lid on the jar accounts for the liquid having not evaporated: it had corroded to the neck, hermetically sealing off the jar’s contents until the tomb was excavated thousands of years later. What is equally amazing is that these “well-aged” liquids sometimes have the characteristic fragrance of a fine rice or millet wine made the traditional way, slightly oxidized like sherry but also perfumy and aromatic.

The analysis of the Changzikou liquid revealed that two aromatic compounds–camphor and α-cedrene–were present in the ancient beverage, in addition to benzaldehyde, acetic acid, and short-chain alcohols characteristic of rice and grape wines. Stable 13C and 15N isotope measurements identified the beverage as rice-based. Based on a thorough search of the chemical literature, camphor and α-cedrene might have originated from a specific tree resin (China fir = Cunninghamia lanceolata (Lamb.) Hook.); a flower of the chrysanthemum family; or an aromatic herb, specifically Artemesia annua and/or A. argyi in the wormwood/mugwort genus. If an Artemesia species explains the presence of camphor and α-cedrene, then the plant’s leaves had probably been steeped in the rice wine, as is still done in TCM. An open vat found in the Changzikou Tomb, which was filled with aromatic Osmanthus fragrans (tea olive) leaves and held a ladle, pointed to this method of preparation of the ancient beverage, which is still popular today for making flavored or medicinal tisanes and drinks.

Of the possible ingredients and additives identified in the Changzikou wine, the two species of Artemisia stood out because of their long-standing importance in Traditional Chinese Medicine up to the present. They are a primary focus of our Archaeological Oncology program.

Biomolecular archaeological evidence–which is increasingly retrievable from ancient containers using microchemical techniques–points to a long history of medicinal and anticancer remedies that were tried, tested, and sometimes lost throughout the millennia since the human species emerged in Africa and spread out across the planet starting around 100,000 years ago. Our ancestors might well have discovered empirically some of the most potent and medicinally effective plants in their environments, especially in periods of experimentation as epitomized by the Neolithic Revolutions beginning 10,000 years ago, after the end of the last Ice Age. Plants, including herbs, tree resins, and other organics were ideally dissolved in and dispensed by ancient fermented beverages, such as wine and beer

Archaeological Oncology can help speed up the drug discovery process and perhaps recover some of these lost remedies.

2010 P. E. McGovern, M. Christofidou-Solomidou, W. Wang, F. Dukes, T. Davidson, and W.S. El-Deiry. Anticancer Activity of Botanical Compounds in Ancient Fermented Beverages. International Journal of Oncology 37(1), 5-21.

P. E. McGovern, Armen Mirzoian, and Gretchen R. Hall

2009 Ancient Egyptian Herbal Wines. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106:18: 7361-7366.

P. E. McGovern, J. Zhang, J. Tang, Z. Zhang, G. R. Hall, R. A. Moreau, A. Nuñez, E. D. Butrym, M. P. Richards, C.-s. Wang, G. Cheng, Z. Zhao, and C. Wang

2004 Fermented Beverages of Pre- and Proto-Historic China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 101.51: 17593-17599.